afootwego-03-hydration–it-keeps-us-alive

afootwego Posts + Stories template

…for people who love to walk…

Supporting Mindful and Responsible Travel

The afootwego Travel Sense Post about the importance of hydration

Hydration – It Keeps Us Alive and Well

May 2024

14

More than 50% of the adult human body is water, while around 80% of our brain mass is water. Travel, especially air travel, exposes us to dehydration in a number of ways.

Unfortunately, many guidelines about hydration are generalised, and in some cases are quite dubious.

A Quick Outline

In this Post, we shall explore:

Without Water There Is No Life!

We all know that our body depends on water to survive.

That’s because around 55% of the adult human body is water.

Male bodies generally have slightly more water content than females.

An average Australian woman of 71 kg (157 lb) would hold approximately 31 litres (6.8 UK gallons, 8.2 US gallons) of water in her body.

About 90% of her 5 litres (4.4 UK quarts, 5.3 US quarts) of blood will be water.

Some sources suggest that around 80% (75-85%) of our brain mass is actually water.

Mild dehydration can occur when we lose just 1.5% of the water in our body.

A loss of just 1% of water from our brain can cause a drop in our brain function, such as concentration, and short-term memory.

My Travelling Companion’s Dehydration

In early 2019 I visited Singapore on a mission to walk some of the Garden City’s wonderful nature trails.

On the first morning, we set out bright and early on the MacRitchie Reservoir Boardwalk/Tree Top route, with our hydration packs, hats, sunscreen, insect repellent, snacks, first aid kit, etc., etc.

We had come from a Melbourne summer, so Singapore’s warm temperatures were no problem, although the humidity was different. Having been an expat resident of Singapore some years previously, we were aware of that.

The lake-side walk around the reservoir was very pleasant. Then, as the sun began to climb in the sky, the temperature also rose, and I was soon sipping on my hydration pack.

As we moved on to the tree top section, the humidity seemed to increase once we were beneath the jungle canopy. Now my hydration pack was in more demand.

After crossing the 250-metre tree top bridge, we came across several sections of wooden stairs, some of which were quite steep. Working hard, I kept at my hydration pack.

By the time we reached the end of our trail, we had covered around 12 km (7½ miles), and we were both very wet from perspiration. I was also feeling rather warm. When my travelling companion took off his hat, I could see he was flushed cherry-red.

"Are you OK ?", I asked, "Have you been using your hydration pack ?"

It turned out he had been conserving his water, in case something happened, and it took us longer to finish our walk. While I chastised him for doing that, I realised that as a former soldier, he was doing a bit of 'what-if ' thinking.

Now he needed to re-hydrate. After a short bus ride, we were soon at the Adam Road Food Centre. Here, with a generous serve of bubble tea, followed by 'seconds' plus some jelly-cake, he began to rehydrate, and shortly his normal complexion started to return.

What I learned, or perhaps 're-learned ', from this episode, was how high humidity makes it hard for our bodies to cool from perspiration alone. Because Singapore’s humidity is usually over 80%, once I had warmed up, the more I drank, the more I perspired. But, it wasn’t until I reached the cool air of the Food Centre, that I began to feel comfortable.

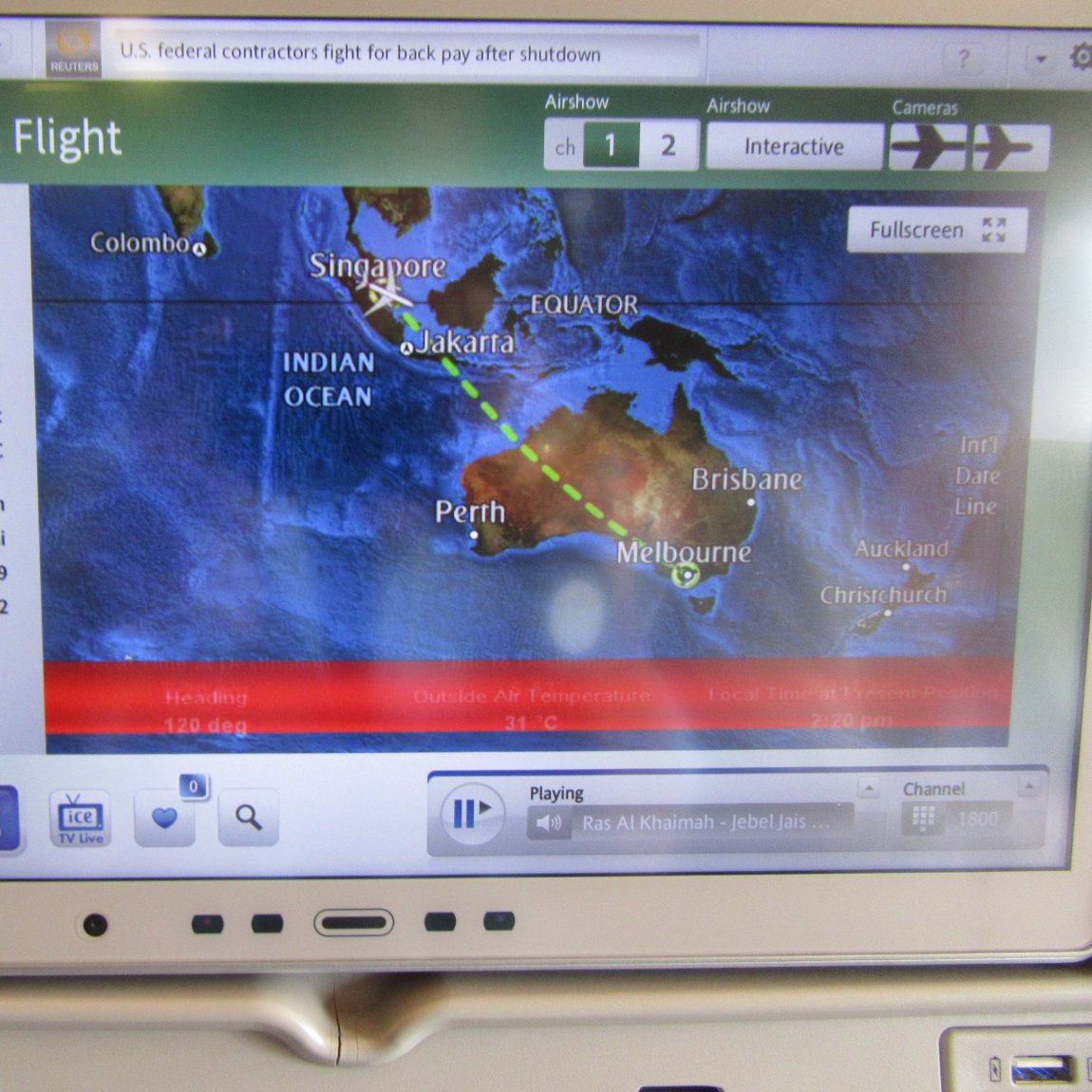

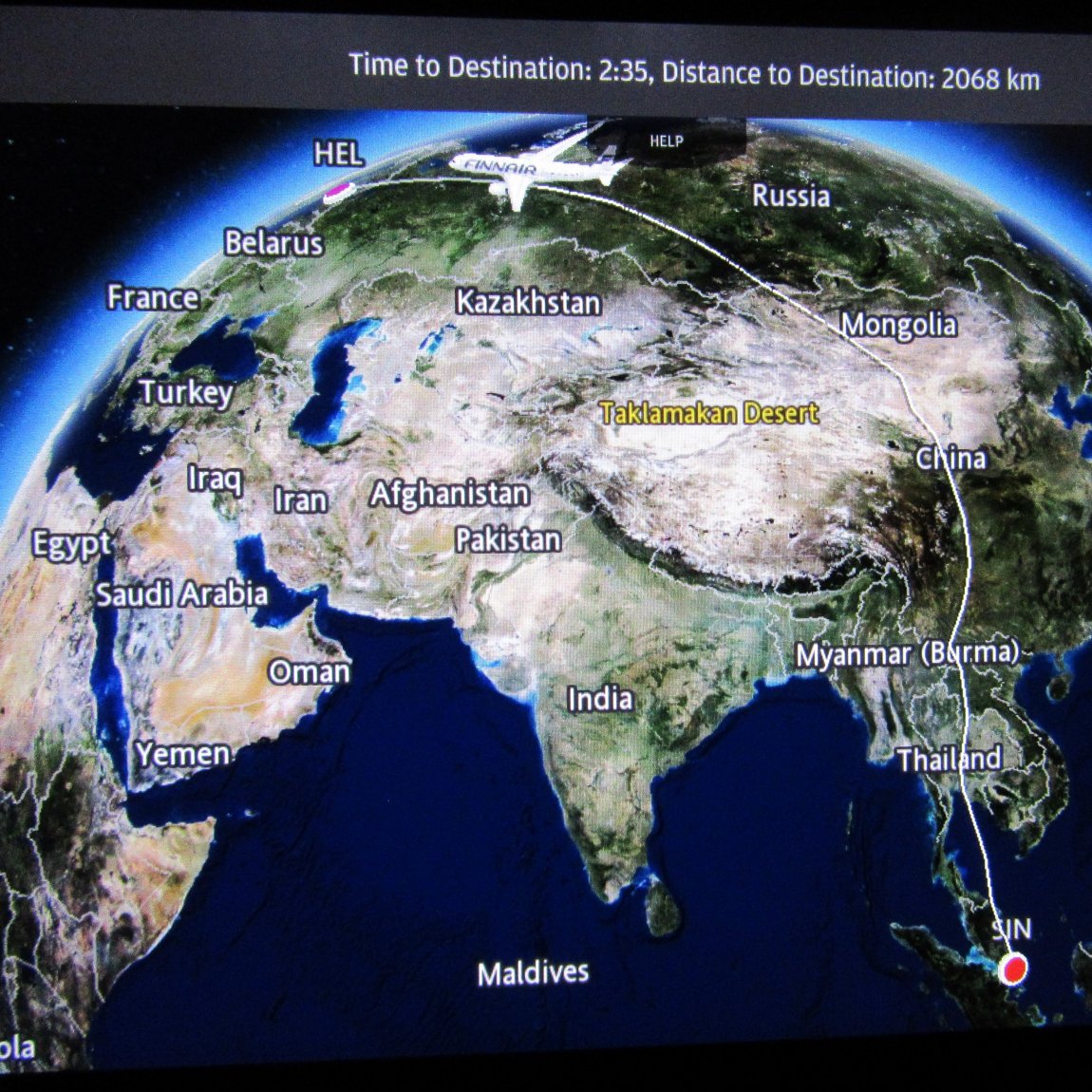

Me, and In-Flight Dehydration

Some years back, I travelled with my Mum to Scandinavia. On our 13-hour long-haul flight from Singapore to Zurich, we departed shortly before midnight. I wanted to get a good sleep, so I did not hydrate before the flight. Once on board, I put on a sleeping mask, and went to sleep.

When I awoke several hours into the flight, the cabin was in darkness, and I had a splitting headache. I was in the centre aisle, hemmed in with sleeping passengers on either side of me, so I was reluctant to disturb anyone.

Eventually, the cabin lights came on, as the crew began to rouse their sleeping passengers for breakfast. At last, I could get to the water fountain. However, the damage was done, as my bathroom stop showed.

My 'water ' was very dark, my head still felt like it was splitting, and I had no energy. I was certainly at least mildly dehydrated. I remember thinking: "Great! And when we land, we have a quick connection to make to Stockholm. I won’t do this again !"

For me, whenever I travel abroad from Australia, the only option is flying. To Asia, this is usually for at least 8 hours; to Europe it is a journey of around 24-hours, sometimes longer. And, because I hate using the inflight bathrooms, especially when the plane is full, I usually try to keep my drinking during the flight to a minimum.

Flying is BAD for Our Hydration Levels

For travellers, long-haul* flights mean dehydration, and there is little we can do to avoid it (* long-haul = lasting longer than 6 hours).

So, if we can’t avoid in-flight dehydration, understanding how and why this happens helps us to put in place strategies to cope.

In simple terms, the cabin of a passenger airliner is pressurised, using air from outside of the plane, as it travels. Air being drawn into the plane from high-altitudes is very dry, which reduces the humidity within the cabin.

As the flight progresses, the main source of moisture within the cabin is passenger respiration, and the resulting condensation. Typically, during flight the cabin humidity will be around 10-20%. This compares with 'safe ' office building humidity levels of 30-40%.

Cabin pressure is usually equivalent to an altitude of 8,000 feet (or 2,500 metres). For newer airliners, such as the Airbus A350 and the Boeing 787 Dreamliner, this is about 6,000 feet. These new generation airliners can also use a higher humidity level of around 25%, as their carbon-fibre body is less prone to corrosion, from moisture in the cabin.

At 8,000 feet, the amount of 'effective ' oxygen in the air is significantly reduced, from ≈21%, down to ≈15½%. At 6,000 feet (or 1,800 metres), oxygen content is at 16½%.

The reduced oxygen levels within the cabin cause passengers to breathe more quickly (called hyperventilating), which means more body moisture is being exhaled. The dry cabin air also extracts surface moisture from passenger’s faces, and other exposed skin areas. Along with the skin, our eyes and nose are likely to become dry.

I have read "On an average 10-hour flight, men can lose about two litres of water, and women around 1.6 litres& quot;. For an Australia-Europe flight, this means a passenger could lose around 10% of their body water. Unless it is quickly replaced, that takes us way beyond 'mild ' dehydration.

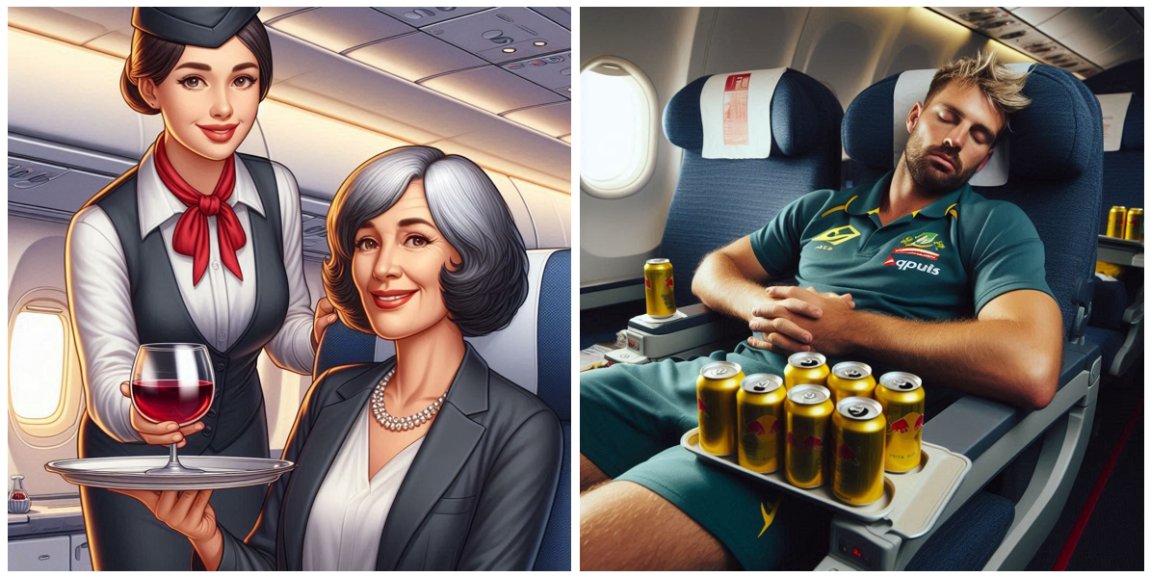

Alcohol and Dehydration

For those of us who like to enjoy an alcoholic drink (wine, beer, spirits, liquors), every sip we take will contribute to dehydration. Alcohol is a diuretic, and causes our bodies to remove fluids from our bloodstream. Its effects can be countered by drinking some water, preferably along with the alcohol.

When we chose to drink alcohol while flying, especially on long-haul flights, we set ourselves up for a dehydration 'double whammy '!

Firstly, the dry atmosphere within the aircraft cabin is already having an impact of our body, drawing moisture into the dry cabin air. Now, our fluid loss will be aggravated by the frequent trips to the 'loo' that we are forced to take, as our kidney’s go into overdrive. Dehydration, and its companion, Jet Lag, are both guaranteed!

In addition to the above 'double whammy ', there is some evidence that the low cabin air pressure causes thinning of our blood, which diminishes our body’s ability to absorb oxygen. This can increase the effects of alcohol, such as causing light-headedness, or hypoxia.

And this is the point where our behavior can become unruly, leading to all manner of complications.

Indicators of Dehydration

If we don’t take enough fluids onboard during the day, some extent of dehydration is inevitable. This can happen anywhere – at home, or at work, as well as while travelling.

But we are not just losing water, we are also losing electrolytes, which are essential minerals that our bodies use, such as sodium, calcium, and potassium. This is especially so when we are under physical exertion.

Classic indicators that we are becoming mildly dehydrated include: headache, feeling light-headed, a dry mouth, feeling thirsty, short-term memory loss, drowsiness, lack of energy, becoming irritable, reduced urination, dark and smelly urine, and a lack of perspiration during vigorous activity.

Some of these indicators were obvious in my two anecdotes above. Curiously, the 'flushed cherry-red ' complexion of my travelling companion was actually a quite normal response to physical activity.

When we lose electrolytes without replacement, we are soon in trouble: fatigue, nausea, irritability, blood pressure changes, muscle cramps, low energy, even impaired blood clotting and heartbeat.

If we go beyond mild dehydration, early signs include lack of perspiration, and dry, shrivelled skin. At this point, medical intervention is likely to be required, as soon as possible.

We can also suffer dehydration from diarrhoea and/or vomiting. While this is known as the 'traveller’s curse ', we don’t need to be travelling to encounter this misfortune. A case of severe food poisoning, contracted in Melbourne, led to me needing help from my doctor.

I have also had my experiences with the traveler’s curse. The worst happened in late December 1999. I boarded a flight in Hong Kong, at around 02:00 a.m., bound for London, some 14½ hours away. Soon after departure, a snack, containing chicken, was served.

About 3 hours later, I was in trouble. Both ends were about to fire! The next 10 hours were amongst the most uncomfortable of my life – ever! At least, when I arrived, there was not much left for my system to eject!

After seeking emergency medical treatment from a London Doctor, the remedy was literally a 'pain (jab) in the butt !'

Rehydration and Recovery

While it can take just a few minutes to begin rehydrating our body, the first 'rule ' of rehydration is '

When water and food are mixed (consumed) together, it can take a couple of hours for the water to be absorbed, to rehydrate your body. When we drink water on an empty stomach, it will enter our bloodstream within five minutes.

Water is not the only fluid to take for rehydration. Research shows that dairy milk, which contains natural electrolytes, carbohydrates, and proteins, is one of the most effective beverages for hydration. Coconut water is another option, as it provides much-needed water, plus electrolytes, and a few carbohydrates.

When we are rehydrating, the temptation can be to literally pour the fluid down our throat, i.e, to 'chug ', or gulp. However, if we can '

Bananas are a convenient food to help treat mild dehydration, as they contain high quantities of potassium, which is an electrolyte. When our body loses too much water through perspiration, potassium is also lost. Eating bananas when we are dehydrated can also help alleviate muscle cramps.

Watermelon is one of the most hydrating foods we can eat, as it is over 90% water. It is also a ready source of fibre, important nutrients, including Vitamin A and C, and electrolytes, such as potassium, magnesium, and phosphorus.

For mild, or even moderate cases of dehydration, once we start rehydrating, we can expect our body to be feeling better after just a few hours. However, depending on the extent of the dehydration, full rehydration may require more than a day.

The Keys to Hydration

To keep our body, including our brain, adequately hydrated, throughout the day we need to regularly take in fluid. This includes fluid from foods, such as fruits and vegetables. It is noted that individual needs will vary, depending on the local climate, altitude above sea level, our activity level, age, body weight, and other influences, e.g. a breast-feeding Mum.

So, "how much water per day does a person need ?". Well, I asked Dr Google, and the first page of search results were perplexing. There are several different units of measure being used, such as cups, glasses, fluid ounces, and litres/liters. However, the US and UK measures for a 'cup' are different; the UK 'imperial ' cup is different to a 'metric ' cup; and the UK also uses both 150 ml and 200 ml glasses!

So, speaking as an 'ordinary ' Australian, it is no "bloody " wonder that the punters are confused! There is no way of knowing which horse to back in this race – some of them have only got three legs!

Fortunately, the one measure that appears to be safe from all of this nonsense is the litre/liter. It’s apparently the same amount, just spelled differently in different countries. In the 'Litre ' we will trust.

Recommended Daily Fluid Intake

The following table shows the recommended daily fluid intake (Litres/Liters), for adults in four different regions of the world:

Broadly speaking, it is recommended that the daily intake of fluids for women should be 2 to 2.75 litres/liters, and for men 2.5 to 3.70 litres/liters, except for people from the UK.

Curiously, the best guidance I could find for Singapore was 2.0 litres of fluid per day, for adult women and men alike.

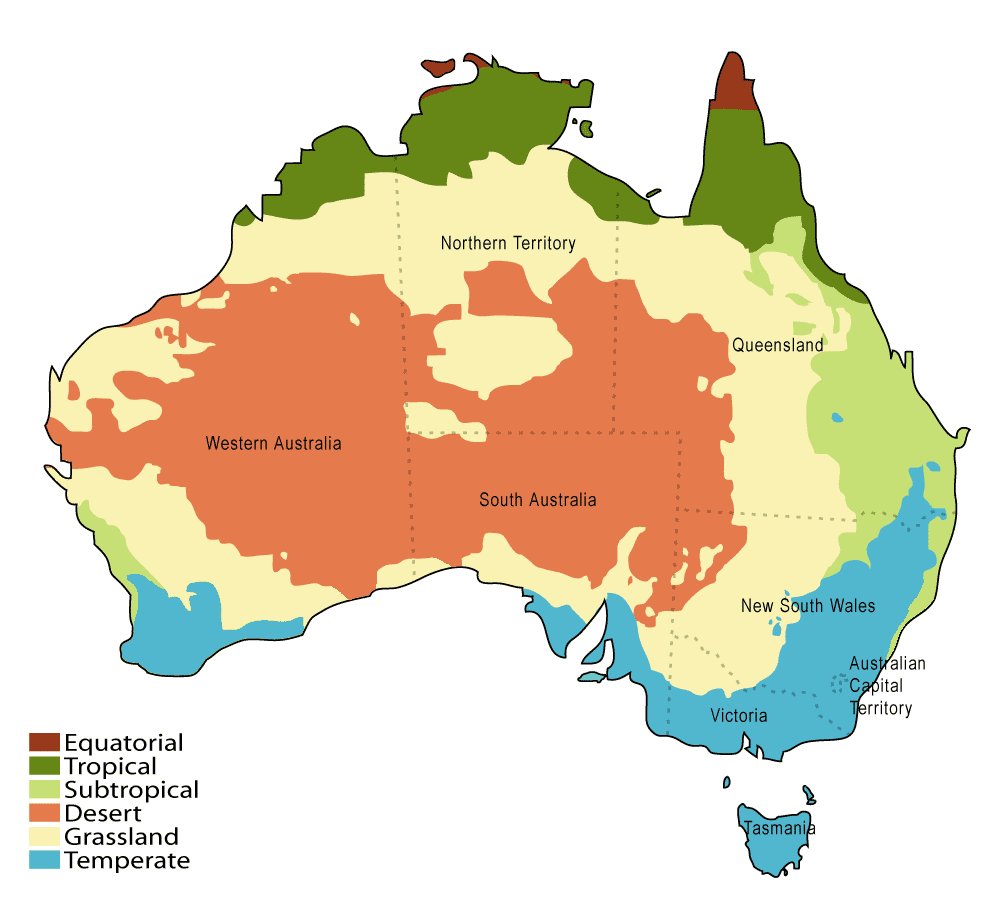

When I consider the extensive range of the continental climate zones in the first three regions shown above, I would certainly expect some intra-regional variations for daily intakes of fluid.

Climate zones in Australia range from the Equatorial and Tropical of the far north, to the Arid Desert of central Australia, and the Cool Temperate and Alpine of Tasmania. Daily fluid needs will vary considerably across Australia, from north to south, and from east to west.

Speaking again as an Australian, it seems to me that some of the 'expert ' authors of a number of the health advisory pieces wouldn’t know their backside if they fell over it in the street! Their very 'generalised ' content perhaps fills some bureaucratic requirement, but it offers little real 'informational ' value to the reader.

Perhaps the most useful 'general rule ' about hydration that I have seen is a simple calculation. To know how much fluid we need per day, we multiply our weight in kg by 0.033. As an example, if I am 70kg, I need to consume about 2⅓ litres of fluid each day,

However, that does not take into account things like local climate.

Now, personally, I’m not one for drinking cold water neat. So, I am thankful that there are other options, such as herbal teas, natural fruit drinks, and even fruits like watermelon and cucumber, and vegetables like celery and lettuce.

According to some, even tea and coffee, when consumed 'in moderation ', don’t appear to increase the risk of dehydration (Mayo Clinic).

Your Take-outs

Here are some key points about hydration and rehydration:

- Our personal hydration needs are affected by a number of things, including our gender, weight, age, activity level, and the local climate

- Many guidelines for keeping ourselves hydrated are generalised, and in some cases may be quite dubious

- Use the '

0.033 rule ' for calculating your primary daily fluid need, based on your body weight; you will also need to consider your activity level, and the local climate - Hydration is not just about water, rather it is about all of the fluids we take in, which includes various fruits and vegetables

- Becoming thirsty is likely to be a sign that you’re already slightly dehydrated; the effects of even mild dehydration can cause a drop in our brain functions, such as short-term memory, and also concentration

- Sipping our fluid or beverage, rather than gulping or 'chugging ' it, does not overload our kidneys, and allows our body to retain more water

Fluid first, then food : water that we drink without taking in any food can be absorbed by our body in a matter of minutes; eating food and drinking together results in the food being digested first, before the water is absorbed- Fluids such as milk and coconut water contain natural electrolytes, carbohydrates, and proteins, making them ideal for rehydration

- Fruits such as watermelon and cucumber, and vegetables like celery and lettuce, all have a very high fluid content, plus they contain various vitamins and electrolytes

What about you? Do you have some other travel hydration tips? I would love to hear about your ideas, and any travel experiences you have had with hydration.

Your Feedback, please…

Firstly, my thanks to you, for reading my post.

Now, the really BIG question is:

“What value has this Post offered you? “

Has it helped you, or do you need more information?

If you wish to offer some feedback, or to read the feedback from others, please follow the link below to the Feedback Page:

Why Your Feedback is Important to Me

In real life, I am an agile Change Manager, so I know that feedback is an essential part of the improvement process.

Your feedback can help me improve both the content of this Post, and also of future Posts.

If you have a thought, or a question, about the post content, or if you would like to provide feedback about something else, please follow the link to the Feedback Page.

I do look forward to hearing from you, especially if we can make improvements that will help fellow travelers on the road.

Marlene

Please note, before any feedback is posted, it will be moderated. When I am moderating, I may need to contact you, which is why I ask for your email address.

Your email address will

Here is a link to the my afootwego.com CONDITIONS for POST FEEDBACK (2½ mins to read).

Should you wish to peruse them, here are links to my afootwego.com PRIVACY POLICY and Website TERMS and CONDITIONS of USE.

- NOTE:

- This site is specifically designed for responsive display on a mobile device

On devices with wider screens, it will appear as a single, center-aligned column